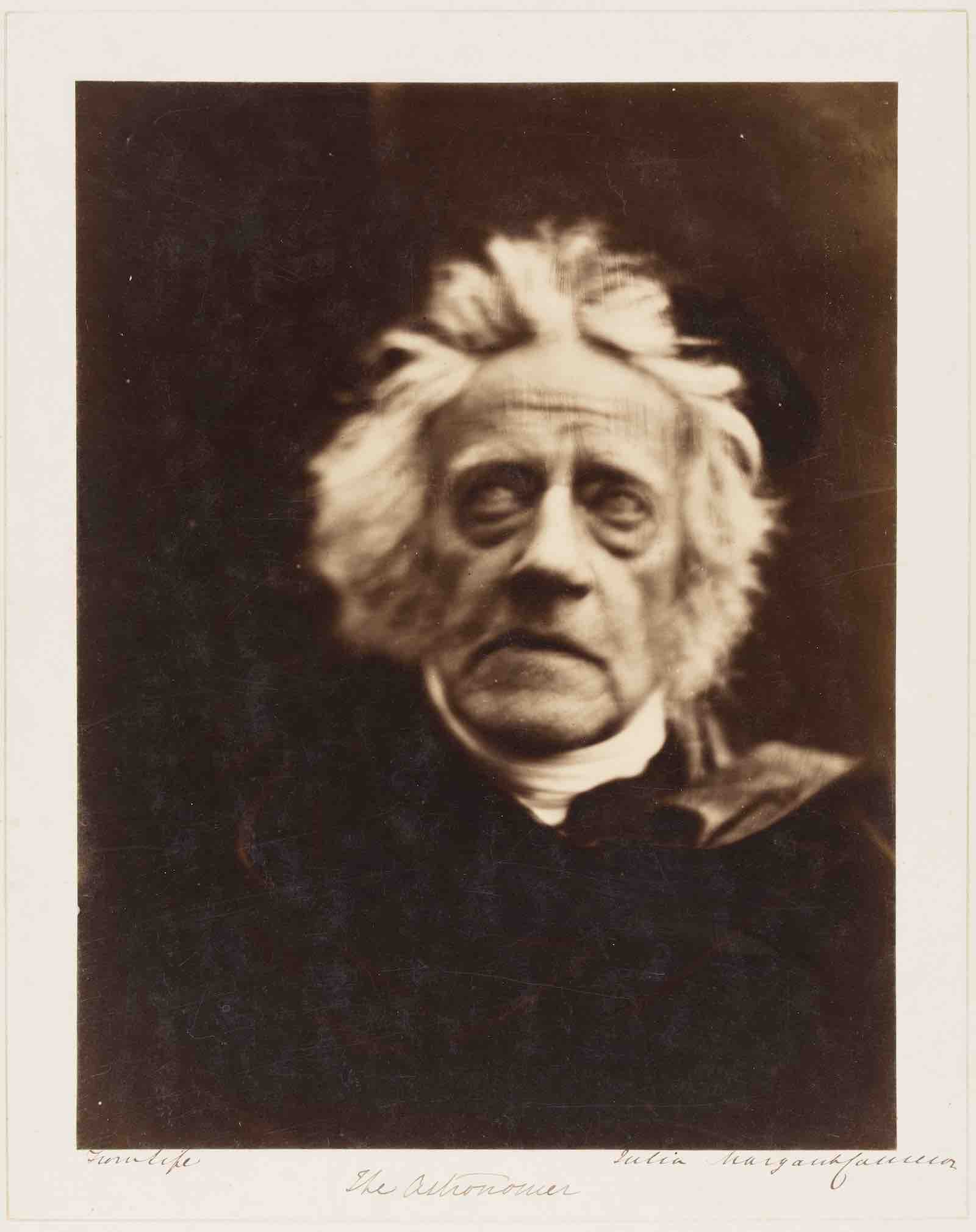

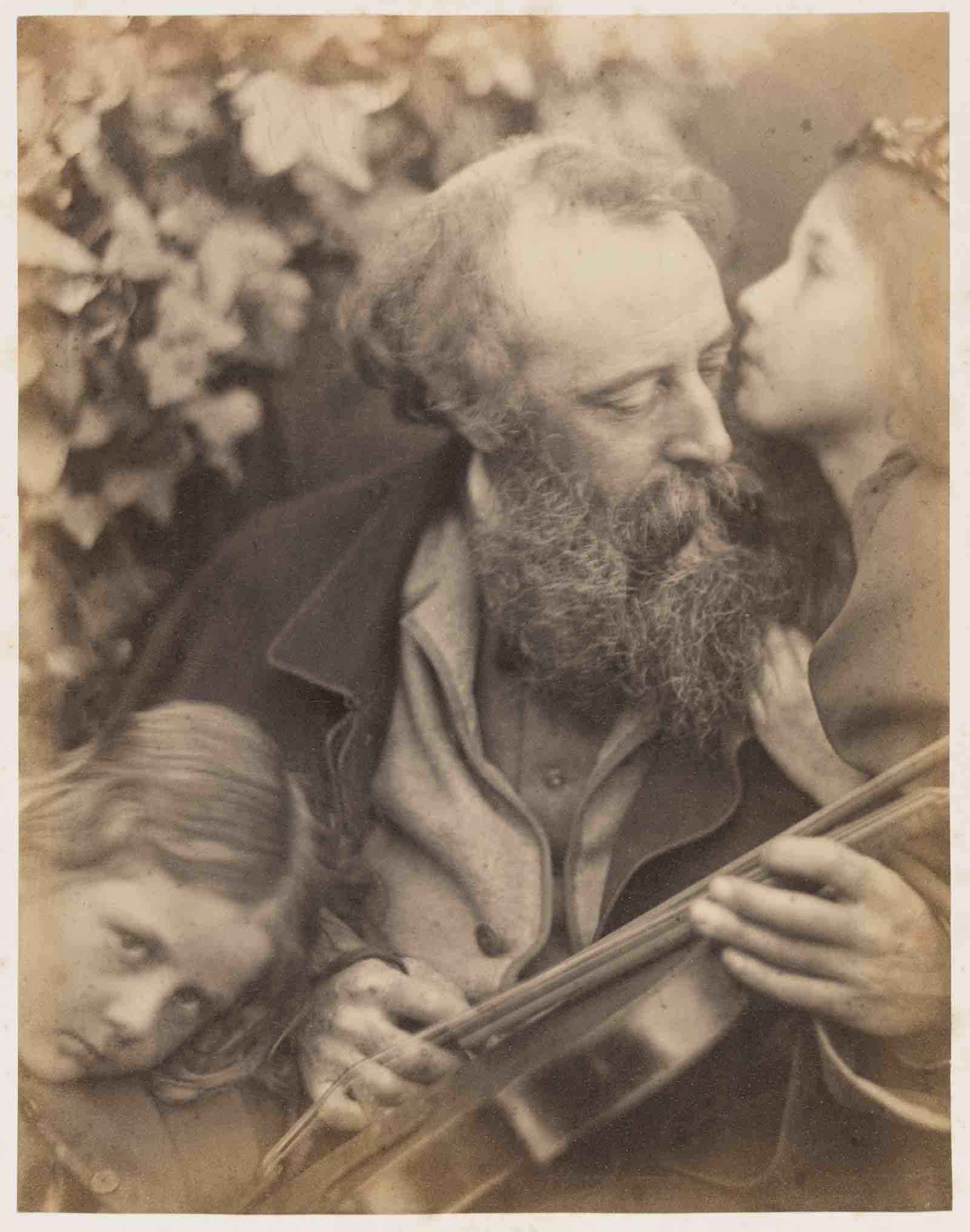

Cameron’s drive helped her become a portraitist of leading writers, artists, and scientists such as Tennyson, Thomas Carlyle, George Frederic Watts, and Charles Darwin, while her absorption in fine art led her to create staged tableaux in a mode that has been perpetually rediscovered by photographers down to the present. Heedless of contemporary conventions of technique, she embraced a style of spontaneous intimacy that distanced her from the photographic establishment. Motion blur, highly selective focus, and even fingerprints on the glass negatives are among the idiosyncrasies of her singular oeuvre.

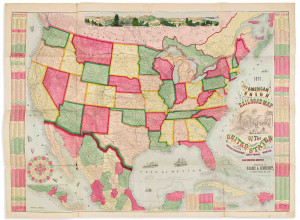

Cameron was quick to exploit publishing and promotional opportunities: At London’s South Kensington Museum (now the Victoria and Albert Museum), she secured not only an exhibition in 1865 but also studio space, and she was the first photographic artist to be collected by the institution.

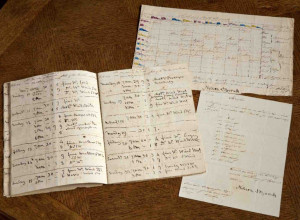

Also included in the exhibition are pages from Cameron’s unfinished memoir Annals of My Glass House (1874) in which she reflects on her artistic journey. Just 21 pages long, the memoir is peppered with literary quotations, humorous stories, and celebrity name-dropping, written in a tone that alternates between self-deprecating and boastful. It was first published posthumously in the catalogue for the London exhibition Mrs. Cameron’s Photography (1889) and has been reprinted many times since.

The exhibition concludes with portraits made in Sri Lanka after Cameron and her husband moved there in 1875. They resemble her previous work in that they are attractive, medium-distance portraits of readily available sitters. But instead of friends or well-known historical figures, the subjects are mainly plantation workers. Her photographic activity was limited there, in part due to difficulties in obtaining supplies.